Closing the Gap began in response to a call for governments to commit to achieving equality for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in health and life expectancy within a generation.

It is the story of a collective journey–a shared commitment to empower Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to live healthy and prosperous lives.

In 2020, there is a greater focus on partnership between governments and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. At the centre of this new way of working is local action, and a determination to make a difference and to achieve change. This Closing the Gap report points to the future, a new path where Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people share ownership to improve life outcomes for current and future generations. It closes off on an era of reporting against targets set by governments.

In partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, we are moving towards a new National Agreement on Closing the Gap setting out priorities for the next ten years.

Closing the Gap

In 2017, the Government began a process to refresh the Closing the Gap agenda. A Special Gathering of prominent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people called for the next phase to deliver a community-led, strengths-based approach. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians are at the centre of this new strategy.

Recognising a formal partnership between government and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people would achieve greater progress in the future, the Prime Minister sought agreement from the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) to a new way of working.

In 2019, all levels of government and a Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations signed a formal agreement to work in genuine partnership. This means shared accountability and jointly developing an agreed framework and new targets. The Partnership is helping to capture the aspirations and priorities of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals and communities in the design of policies and programs which impact them.

The significance of this new partnership is reflected in the establishment of the Joint Council on Closing the Gap. This is the first time a COAG Ministerial Council has included non-government representatives.

As governments work in this new way, there is increasing involvement and support for local communities to set their own priorities and tailor services to their unique contexts. The Indigenous-designed and led Empowered Communities initiative, which is reshaping the relationship between Indigenous communities and governments, is just one example. In a commitment to devolving decision-making as close to the ground as possible, community leaders are directly involved in making recommendations to government about how services and funding align with community priorities. Transparency and data sharing informs a ‘learn and adapt as you go’ approach and underpins local action.

Annual report on progress in Closing the Gap

In 2007, Commonwealth, state, territory and local governments made a commitment to work together to close the gap in Indigenous disadvantage. This led to the National Indigenous Reform Agreement, a significant step toward more coordinated action.

The first Closing the Gap framework outlined targets to reduce inequality in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people's life expectancy, children’s mortality, education and employment. The commitment focused on delivering policies and programs across fundamental 'building blocks' as priority areas, which would underpin improvement. These were: early childhood, schooling, health, economic participation, healthy homes, safe communities, governance and leadership.

The Commonwealth Government has delivered an annual report on progress on Closing the Gap since the National Indigenous Reform Agreement was established.

There has been good progress made in early childhood education. The target to ensure 95 per cent of all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander four year-olds are enrolled in early childhood education by 2025 is on track, with 86.4 per cent of children enrolled in 2018. This means more Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are getting access to learning opportunities that will set them up for a better future. Early childhood is a time of important cognitive and social development. The achievement of this target sets up children to achieve better outcomes across their lives.

Connected Beginnings is an example of a program that has contributed to progress on this target. Integrating early childhood health, education and family support services, including funding local Aboriginal and Community Controlled Health Services to undertake outreach activities on school grounds, it provides children and families with holistic support and timely access to existing services. This helps children meet the learning and development milestones necessary to thrive and make a positive transition to school. There are funded initiatives in 15 Indigenous communities across Australia, with many sites reporting that it has been instrumental in laying the foundation for increased participation in preschool and early childhood education.

The target to halve the gap in Year 12, or equivalent, attainment for Indigenous Australians aged 20‑24 by 2020 is also on track. Year 12 attainment is an important achievement in itself, but it is also a stepping stone to higher education and employment, opening the door to a breadth of opportunities for young people. This is promising for Indigenous employment that has improved slightly but not enough to meet the target. For Indigenous Australians with higher levels of education, there is virtually no gap in employment rates.

Regional University Centres, such as the Wuyagiba Bush Hub Aboriginal Corporation in the Northern Territory, are focused on supporting young people to access higher education on country. Under the leadership of local Elder Kevin Rogers, and Dr Emilie Ens of Macquarie University, the Wuyagiba Bush Hub is providing a curriculum that includes cultural content interwoven with academic skills. In 2019, nine students completed the university preparation course—five of these students have been offered places at Macquarie University and the remaining four at Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education.

Chloe Backhouse, a proud Weilwan and Gamilaroi woman living in Sydney, is benefitting from programs being delivered as part of the Closing the Gap commitment. Chloe participated and successfully completed a traineeship with Camden Council. Chloe learned valuable office and customer service skills while studying for a Certificate III in Business Administration and working at the Camden Council. This experience gave Chloe a strong foundation on which to build a career and led to employment.

These are examples of programs being delivered at a local level to make a real difference in the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. They are all achievements to be celebrated, especially the personal successes of participants. But there remains more to be done.

The child mortality rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children has reduced slightly since 2008, and risk factors related to this target have improved, including attendance at antenatal care and reduced smoking during pregnancy. However, as mortality rates for non-Indigenous children have also improved, this has not yet translated into stronger improvements in Indigenous child mortality rates, and the gap has not narrowed.

Targets to close the gap in school attendance and halve the gap in reading and numeracy and employment by 2018 were not met, although there has been improvement in reading and numeracy and the gap has narrowed across all year levels. More Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are exceeding national minimum standards better positioning them to transition to further study and work. However, about one in four Indigenous children in Years 5, 7 and 9 remain below the national minimum standard in reading, and one in five in Year 3 remain below the national minimum standard in reading.

Since 2006 there has been an improvement in Indigenous mortality rates, driven primarily by improvements in one of the leading causes of death, circulatory disease. However, non-Indigenous mortality rates have improved at a similar pace and the gap has not narrowed. Of concern is a worsening of cancer mortality rates. The Tackling Indigenous Smoking program seeks to address smoking-related cancer and other diseases. It is also Aboriginal-led, community focused and place-based. Local campaigns, such as the one developed by the Flinders Island Aboriginal Association Incorporated, use the experience of local residents and transform community members into champions. Daily smoking among Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over has decreased from 41 per cent in 2012–13 to 37 per cent in 2018–19.

While on almost every measure, there has been progress, achieving equality in life expectancy and closing the gap in life expectancy within a generation is not on track to be met by 2031. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people still have a lower life expectancy than non-Indigenous people.

The Commonwealth, with the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation, and the Australian Medical Association, have negotiated a Primary Health Care Funding Model under the Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme. Over three years, a new funding model will work to deliver primary health care that is appropriate to the unique culture, language, and circumstances of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. In developing a new funding model, the Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service sector informed the design and it is changing the funding model that distributes primary health care grants.

Progress in the overarching life expectancy target is dependent not only on further progress in health, but also in other outcomes such as education, employment, housing and income. There is more work to be done to close the gap in health inequality, including by harnessing the strength of culture as an underlying determinant of good health through identity and belonging, supportive relationships, resilience and wellbeing.

Although it is concerning not all targets have been met, there are positive signs that working together can accelerate progress and achieve better outcomes.

The chapters that follow provide more detail on the most recent data against each of the seven targets. They show many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people continue to experience disparity with non-Indigenous people in important areas of their lives. That disparity is even greater for people living in remote areas. It is important to acknowledge the truth of this, and continue to build better data at the regional level and expand opportunities for shared-decision making, so that we move forward with a clear understanding of the challenge.

Working in Partnership and a new framework for Closing the Gap

To rise to this challenge, the Closing the Gap framework is moving toward a strengths-based agenda—one that partners with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, enables more community control and embeds shared decision-making.

The Commonwealth, state,and territory governments, and the Australian Local Government Association, in partnership with representatives of the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations, are working to develop the new Closing the Gap framework and targets to set the direction for the next ten years.

'Never have Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peak bodies from across the country come together in this way, to bring their collective expertise, experiences, and deep understanding of the needs of our people to the task of closing the gap…We have an unprecedented opportunity to change the lived experience of too many of our people who are doing it tough.'

Ms Pat Turner AM, CEO of the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation

The new national agreement will be one where all parties commit to achieving the priorities and targets—where there is greater accountability to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities for progress.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who participated in consultations during the Closing the Gap Refresh process expressed their desire for a strong and inclusive partnership and a greater say in the design and delivery of programs and services. The partnership is changing the conversation. It is becoming clear that priorities for the future involve creating more opportunities for shared decision-making, improving access to and collection of data to increase transparency, building the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-controlled services sector, and ensuring all mainstream institutions deliver programs and services that meet the needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

A framework will be developed to incorporate these important elements, and provide indicators to monitor progress toward outcomes and incorporate regular independent oversight of implementation.

Stories of local action to create change

There are many examples that demonstrate what can be achieved at a local level when governments work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

A partnership in New South Wales and Victoria is making a real difference to employment opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. As part of the Echuca/Moama Aboriginal Workforce Development Strategy a steering committee of industry, land councils, elders and community leaders, and all levels of government has worked together to deliver 45 new jobs.

The Jawoyn Association Aboriginal Corporation is another example of all levels of government, business, local Aboriginal people and the non-government sector working together to stimulate the local economy and improve social outcomes.

The Multi-Agency Partnership Agreement between the Gurindji Aboriginal Corporation, Northern Territory Government and the National Indigenous Australians Agency is also delivering real benefits to the local people of Kalkaringi. The partnership has resulted in six new local jobs and delivery of key infrastructure projects to upgrade housing and community facilities. It also supports the continuation of the Freedom Day Festival celebrating local culture and history, commemorating the Wave Hill walk off which put Aboriginal land rights onto the national agenda in the 1960s, and is a significant source of revenue for the community.

These examples show that it is possible to work together more effectively to get tangible outcomes.

For more than a decade, Commonwealth, state, territory and local governments, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous organisations, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities have been working to improve outcomes. Some progress has been made and a stronger partnership approach will accelerate these improvements, with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people taking greater ownership over the design, development and delivery of policies and programs that impact their lives.

In 2005, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner’s report recommended that Commonwealth, state, territory and local governments commit to achieving equality in health and life expectancy outcomes within 25 years. The data contained in this report shows that more work is needed. These are complex issues needing persistence and flexibility. We have seen that solutions are most successful when they are led by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. A genuine partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, which values their expertise and lived experience, is integral to achieving equality in life outcomes.

Closing the gap was expected to take a generation—the effort must continue.

Progress against the Targets

Progress against the Closing the Gap targets has been mixed over the past decade.

As four targets expire, we can see improvements in key areas, but also areas of concern that require more progress.

- The target to halve the gap in child mortality rates (by 2018) has seen progress in maternal and child health, although improvements in mortality rates have not been strong enough to meet the target.

- The target to halve the gap for Indigenous children in reading, writing and numeracy within a decade (by 2018) has driven improvements in these foundational skills, but more progress is required.

- There has not been improvement in school attendance rates to close the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous school attendance within five years (by 2018).

- The national Indigenous employment rate has remained stable against the target to halve the gap in employment outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians within a decade (by 2018).

Two of the continuing targets are on track.

- The target to have 95 per cent of Indigenous four year‑olds enrolled in early childhood education (by 2025).

- The target to halve the gap for Indigenous Australians aged 20–24 in Year 12 attainment or equivalent (by 2020).

However, the target to close the gap in life expectancy (by 2031) is not on track.

Jurisdictions agreed to measure progress towards the targets using a trajectory, or pathway, to the target end point. The trajectories indicate the level of change required to meet the target and illustrate whether the current trends are on track. See the Technical Appendix for further information.

When the Council of Australian Governments established the National Indigenous Reform Agreement as a framework for the Closing the Gap targets, it was recognised that improvements in data quality were necessary to support reporting and measurement of progress. Work has been undertaken to improve the data collections that inform the targets, such as the Census, deaths registrations, and the perinatal data collection.

The need to continuously improve the quality of the data is important for strengthening the evidence base. However, this also impacts upon the measurement of outcomes and poses challenges for interpreting trends in the targets. These issues are touched on in the report and in the Technical Appendix.

Trend results in this report are statistically significant, unless indicated otherwise. See the Technical Appendix for more information.

Progress across states and territories

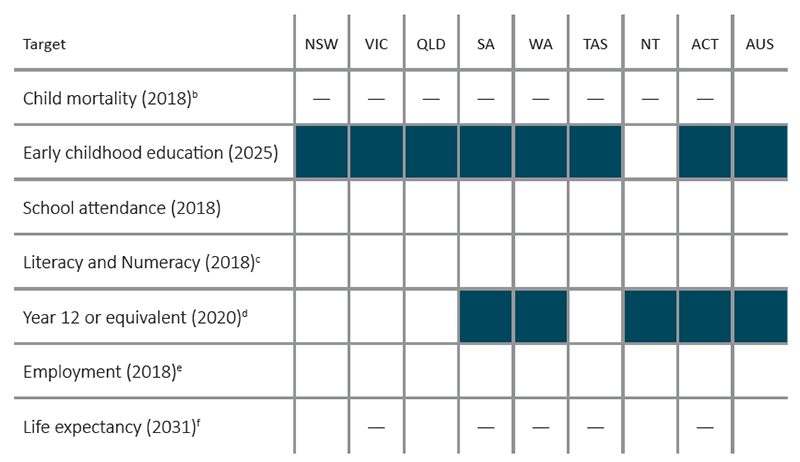

Progress against the targets for each state and territory varies, and is summarised in Table 1.1. This table serves as a guide to progress, but should not be used in isolation as there are limitations for each target trajectory, and for the data sources used to measure outcomes. More detailed analysis of progress in each of the target areas is found in the chapters of this report.

Notes:

(a) A blue box indicates the target is on track. A dash indicates the data are either not published or there is no agreed trajectory. The other targets are not on track or have not been met. For more information on the target trajectories see the Technical Appendix.

(b) Due to the small numbers involved, state and territory trajectories were not developed for the child mortality target. The national target reflects results for New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory combined, which are the jurisdictions considered to have adequate levels of Indigenous identification in the deaths data suitable to publish.

(c) For the purposes of this summary table, states and territories are considered to have met the target if more than half of the eight National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) areas (Years 3, 5, 7, and 9 reading and numeracy) were met in each jurisdiction.

(d) The Census is the primary data source for the target which was published in the 2018 Closing the Gap Report.

(e) Progress against trajectories for the employment target was assessed using the 2018–19 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey data.

(f) Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander life expectancy are published every five years for New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory only. Due to the small number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander deaths in Victoria, South Australia, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory, it is not possible to construct separate reliable life tables for these jurisdictions. However, as indicated in the table, only three jurisdictions have agreed life expectancy trajectories to support this target.

View the text alternative for Table 1.1.